PARENT OWNS THE PROBLEM

- A child is often late for dinner.

- A child is interrupting your conversation with a friend.

- A child calls you at work several times every day.

- A child has left his toys on the living-room floor.

- A child appears about ready to tip his milk over onto the rug.

- A child is demanding that you read her one more story, then another, then another.

- A child plays her music too loudly.

- A child is not carrying his load of work around the house.

- A child uses your tools and doesn’t put them back.

- A child drives your car too fast.

Parents have several alternatives when they own the problem: 1. They can try to modify the child directly. 2. They can try to modify the environment. 3. They can try to modify themselves.

Komunikace k dítěti když má rodič problém

Používát JÁ-SDĚLENÍ NIKOLIV TY-SDĚLENÍ..

špatně:

Sending a “Solution Message”

- ORDERING, DIRECTING, COMMANDING

“You go find something to play with.”

“Turn that music down!”

“Be home by 11:00.”

“Go do your homework.” - WARNING, ADMONISHING, THREATENING

“If you don’t stop, I’ll scream.”

“Mother will get angry if you don’t get out from under my feet.”

“If you don’t get out there and clean up that mess, you’re going to be sorry.” - EXHORTING, PREACHING, MORALIZING

“Don’t ever interrupt a person when she’s talking.”

“You shouldn’t act that way.”

“You shouldn’t play when we’re in a hurry.”

“Always clean up after yourself.” - ADVISING, GIVING SUGGESTIONS OR SOLUTIONS

“Why don’t you go outside and play?”

“If I were you, I’d just forget about it.”

“Can’t you put each thing away after you use it?”

These kinds of verbal responses communicate to the child your solution for her— precisely what you think she must do. You call the shots; you are in control; you are taking over; you are cracking the whip. You are leaving her out of it. The first type of message orders her to employ your solution; the second threatens her; the third exhorts her; the fourth advises her.

Parents ask,

“What’s so wrong with sending your solution—after all, isn’t she causing

me a problem?”

True, she is. But giving her the solution to your problem can have these

effects:

- Children resist being told what to do. They also may not like your solution. In any case, children resist having to modify their behavior when they are told just how they “must” or “should” or “better” change.

- Sending the solution to the child also communicates another message, “I don’t trust you to select your solution” or “I don’t think you’re sensitive enough to find a way to help me with my problem.”

- Sending the solution tells the child that your needs are more important than hers, that she has to do just what you think she should, regardless of her needs (“You’re doing something unacceptable to me, so the only solution is what I say”).

If a friend is visiting in your home and happens to put his feet on the cushions of one of

your new dining room chairs, you certainly would not say to him:

“Get your feet off my chair this minute.”

“You should never put your feet on somebody’s new chair.”

“If you know what’s good for you, you’ll take your feet off my chair.”

“I suggest you do not ever put your feet on my chair.”

This sounds ridiculous in a situation involving a friend because most people treat

friends with more respect. Adults want their friends to “save face.” They also assume that

a friend has brains enough to find his own solution to your problem once he is told what

the problem is. An adult would simply tell the friend her feelings. She would leave it up

to him to respond appropriately and assume he would be considerate enough to respect

her feelings. Most likely the chair owner would send some such messages as:

- “I am worried that my new chair might get dirty.”

- “I’m sitting here on pins and needles because I see your feet on my new chair.”

- “I’m embarrassed to mention this, but we just got these new chairs and I’m anxious to

- keep them as clean as possible.”

These messages do not “send a solution. People generally send this type of message to friends but seldom to their own children; they naturally refrain from ordering, exhorting, threatening, and advising friends to modify their behavior in some particular way, yet as parents they do this every day with their children.

No wonder children resist or respond with defensiveness and hostility. No wonder children feel “put down,” squelched, controlled. No wonder they “lose face.” No wonder some grow up submissively expecting to be handed solutions by everyone. Parents frequently complain that their children are not responsible in the family; they do not show consideration for the needs of parents. How are children ever going to learn responsibility when parents take away every chance for the child to do something responsible on her own out of consideration for her parents’ needs?

Sending a “Put-Down Message”

Everyone knows what it feels like to be “put down” by a message that communicates

blame, judgment, ridicule, criticism, or shame. In confronting children, parents rely

heavily on such messages. “Put-down messages” may fall into any of these categories:

- JUDGING, CRITICIZING, BLAMING

“You ought to know better.”

“You are being very thoughtless.”

“You are being bad.”

“You are the most inconsiderate child I know.”

“You’ll be the death of me yet.” - NAME-CALLING, RIDICULING, SHAMING

“You’re a spoiled brat.”

“All right, Mr. Know-It-All.”

“Do you like being a selfish freeloader?”

“Shame on you.” - INTERPRETING, DIAGNOSING, PSYCHOANALYZING

“You just want to get some attention.”

“You’re trying to make me mad.”

“You just love to see how far you can go before I get mad.”

“You always want to play just where I’m working.” - TEACHING, INSTRUCTING

“It’s not good manners to interrupt someone.”

“Nice children don’t do that.”

“How would you like it if I did that to you?”

“Why don’t you be good for a change.”

“Do unto others . . . etc.”

“We don’t leave our dishes dirty.”

They point the finger of blame toward the child.

What effects are these messages likely to produce?

1. Children often feel guilty and remorseful when they are evaluated or blamed.

2. Children feel the parent is not being fair—they feel an injustice: “I didn’t do anything

wrong” or “I didn’t mean to be bad.”

3. Children often feel unloved, rejected:

“She doesn’t like me because I did something wrong.”

4. Children often act very resistive to such messages—they dig in their heels. To give up the behavior that is bothering the parent would be an admission of the validity of the parent’s blame or evaluation. A child’s typical reaction would be:

“I’m not bothering you” or

“The dishes aren’t in anybody’s way.”

5. Children often come back at the parent with a boomerang:

“You’re not always so neat yourself ” or “You’re always tired” or “You’re a big grouch when company is coming”

or “Why can’t the house be a place we can live in?”

6. Put-downs make the child feel inadequate. They reduce her self-esteem.

Put-down messages can have devastating effects on a child’s developing self-concept.

The child who is bombarded with messages that deprecate her will learn to look at herself as no good, bad, worthless, lazy, thoughtless, inconsiderate, “dumb,” inadequate, unacceptable, and so on. Because a poor self-concept formed in childhood has a tendency to persist into adulthood, put-down messages sow the seeds for handicapping a person throughout her lifetime.

These are the ways that parents, day after day, contribute to the destruction of their children’s ego or self-esteem. Like drops of water falling on a rock, these daily messages gradually, imperceptibly leave a destructive effect on children.

Efektivní sdělení: I-MESSAGE

- “I don’t feel like playing when I’m tired.”

- “I feel frustrated when I come to pick you up and you’re not there.”

- “I sure get discouraged when I see the mess in the kitchen after I just cleaned it up.”

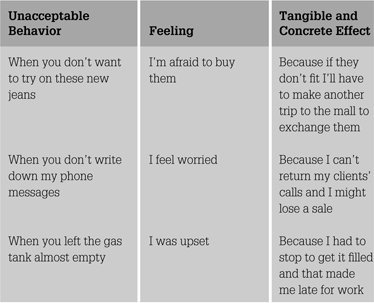

THE ESSENTIAL COMPONENTS OF AN I-MESSAGE

Children will be much more likely to change their unacceptable behavior if their parents send I-Messages containing these three parts:

- a description of the unacceptable behavior,

- the parent’s feeling, and

- the tangible and concrete effect the behavior has on the parent.

[BEHAVIOR + FEELING + EFFECT]

Describing the Unacceptable Behavior

Behavior is something that the child does or says. This part of the I-Message is a simple description of the child’s unacceptable behavior; what she’s doing that bothers you, not your label or judgment of that behavior.

The key here is to remember to describe the behavior, not judge it.

The Parent’s Feeling About the Behavior

When parents send You-Messages, they needn’t identify how they feel as a consequence of a child’s unacceptable behavior. It’s just a matter of blurting out a command, threat, a put-down: “You’re driving me crazy,” “You’re lazy,” etc. Not so when parents try to send an I-Message. Now they need to know how they feel. “Am I angry or afraid or worried or embarrassed or just what?”

“When you didn’t come home from school on time and didn’t call to say you’d be late, I got worried. . . .”

How the Behavior Affects the Parent

Most often, a tangible and concrete effect is something that costs you money, time, extra work or inconvenience. It might prevent you from doing something you want or need to do. It might physically hurt you, make you tired, or cause you pain or discomfort. “When you didn’t come home from school on time and didn’t call to say you’d be late, I got worried and that distracted me from my work.”

When you send a complete three-part I-Message, you tell the child the whole story— not only what she is doing that is giving you a problem, but also what feeling you have about it, and equally important, why the behavior will cause or has caused you a problem.

Here are some examples: